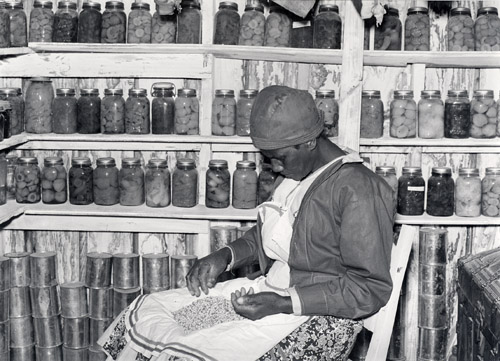

Folk Potters manipulate materials with skills passed from generations of makers before to create pottery turned on a wheel. This art making tradition is embedded in a local identity of handmade crafts, as opposed to self-taught artists, with workshops that generally began as a means of income to supplement farm or labor wages. Yet art making has earned due attention as the process has remained unchanged for ten generations although the need, sale and function of ceramic work ebbs with our modern economy and technology. Before plastic, glass, and tin were readily available for the home, and refrigeration was not an option, clay vessels were the most efficient means to keep dry and wet goods. Once other materials became common, even in rural areas, there was less utilitarian need for potters. Prohibition too put a dent in vessel production since there was little access spirits like moonshine. Crafts people had to rethink what they made to sell, strawberry planters and decorative ceramics became common fixtures at shops. Face jugs played a major part as well but first these ‘whimsies’ were an aside, molded from discarded clay waste. These pots became especially precious commodities to the public only after a Smithsonian Institution documentary on Cheever Meaders in 1967 spurred on ‘ugly jug’ popularity. Folk pottery traditions continue throughout the southeast as a legacy born from backbreaking work, creativity and a passion to continue folk pottery craft tradition.

Today, folk pottery is unique because of the continued ties to local land and makers that keep the tradition virtually unchanged. The labor-intensive process begins with unearthing clay from the land, then cleaned and wedged to remove air pockets. It is divided into sections and thrown on a manually powered treadle wheel. Glazes, refined with a mule turned mill wheel, combines glass, creek water and wood ash to make a smooth even finish to coat pots. The hand built kiln is heated with wood harvested from the area, glazed pots are carefully arranged and sealed inside to burn for a day. It became a community event as people are drawn to watch and entertain potters as they work to maintain the fire. Once cooled, pots are unloaded and put up for sale, usually to anxious costumers who wish to get the first pick.

Cheever Meaders and family in Mossy Creek, Georgia (photo by Doris Ulmann)

The Meaders of White County, Georgia were first farmers. And they are one of many folk pottery families found in the Georgia Piedmont and Highlands area where craftsmen lived near rich sources of clay deposits. Pottery skills were shared not only with immediate family members but also from neighbors, the Meaders learned first from Williams Dorsey and Marion Davidson. John Milton Meaders founded his pottery shop in the winter of 1892-93 where he put three sons, Wiley, Cleater, and Casey to work who then taught younger siblings, Caulder, L.Q., and Cheever, in the soon to be family trade. In the 1930s old Highway 75 linked Florida to New York, Cleater took advantage of travelers by expanding the family business with a shop in Mossy Creek, Georgia, a swampy low land perfect for supplying clay for their pots. Cheever contributed to continuing this legacy in the face of harsh economic times but his retirement in 1957 threatened an end of folk pottery until Arie Meaders, Cheever’s wife, took on the task, reinventing vessels that her husband adapted from utilitarian wares that appealed to aesthetic values of buyers. While Lanier, son of Arie and Cheever, is best known for his face jugs and made significant contributions to popularizing the art form to a wider audience, other notable craftspeople include the Craven, Ferguson, Hewell, and Crocker families all of which are still practicing in the area.

The face jug’s origin in the United States is traced back to the 1850s or earlier. Before then a direct link is blurry, but similar vessels are found across the Atlantic. The human form on vessels can be found in every era and genre of art history. What specific examples are there that inspired face jugs? Toby jugs, a British tradition, are large vessels named after a frequent visitor to pubs. This may explain the anglo branch of potters descending from England. Other theories suggest the gruesome expressions scare children from the jug’s contents, moonshine. Scholars theorize that West African art may have inspired small works created in Edgefield Co., South Carolina, where the appearance may be attributed to Africans brought on The Wanderer, the last known slave ship, which landed off the coast of Georgia in October of 1858. (Examples can be found in the next gallery.) Use of kaolin on jugs, a magical natural resource in Africa, may be evidence of spiritual or mystical purposes. Others believe the emotive faces convey anguish felt by people who were enslaved in South Carolina, or perhaps they were used as grave decorations. There are many theories and no one proven reason why artists decided to decorate these jugs with faces. Prototypes may rest in multifarious source cultures.

Rich sources of natural materials, used for all processes in pottery making, provided local makers with endless resources and sustain Southeastern folk pottery traditions. Millions of years ago the coastline of this area stretched from the Gulf of Mexico up through the center of Georgia to the North Carolina coast. Today the fall line (running from Columbus through Macon to Augusta), what was then the shore, collected rich elements from the sea. The land mass expanded burying sediment to form rich deposits of different types of clay. The most recognizable is Georgia red clay, or Lizella. Kaolin, white clay mined in central Georgia, is frequently used as slip for decorative accents on eyes and teeth. Stoneware clay is most common, dug out of the ground, cleared of hard pieces and plant matter then used to create a variety of wares. The clay is not the only important natural resource that makes folk pottery common in the South. Trees produce timber for fueling daylong kiln burnings. Wood ash is used to mix glazes with ground glass and creek water (or ‘tobacco spit’). Corncobs were dried and used as stoppers to preserve goods kept in the vessels once they were put to use.

The above recording is of a gallery discussion led by Carl Mullis, a folk pottery collector, and Brittany Ranew, educaiton program specialist, at the Georgia Museum of Art on January 11th, 2016.