Last week I led fifteen college freshmen through the permanent collection of the Georgia Museum of Art.

“In 1954 Alfred Holbrook, a lawyer from New York, donated 100 American paintings to the residents of Georgia to begin this museum. We’re always free and open to the public, it’s a nice quiet place on campus. Remember, doors are open late on Thursday nights, making this the perfect place to bring date, wink.”

This usually eases the crowd a bit, and my nerves too, and other than telling folks about Holbrook’s generous gift this is one of my favorite ‘lines’ we give as a tour guides.

Once upstairs, we pause in front of the first work of art.

After a moment of silence I ask, “What is the first step to art interpretation?”

More silence.

“The first step… is to look.”

Again, serious looks break into smiles and the students are begin to get the message, this is not a test.

Now I ask the same from you, experience the image of the art object below by offering it your full attention. Remember, this is not a test, just look.

The above jug, if held, would fit easily cradled in your hands. The eyes and teeth, only slightly smaller than life size, are matte white, elsewhere is high gloss except for the bottom where unglazed pottery shows through. Two other jugs accompany this object in a plexiglass case, another similar face jug and a larger jug, about ten gallons, with no decorations other than a few etched words. The case sits in one corner of a room filled with vernacular decorative arts, worn artifacts with vague histories.

Once the group, and you, have had ample observation time, I ask you to discover information to add to this initial understanding. Usually museums offer this in text near the objects, such details are found on the placard within the case:

Unidentified maker from Edgefield District, South Carolina, Face jug, stoneware and kaolin, ca. 1860

Little information is given it seems. However, group collaboration will help us advance our individual interpretations.

“What do you know about this object?”

“We don’t know who made it.”

Right, the unknowns could tell us more than we first realize. There is no maker's mark or signature verifying who created this jug.

“Why didn’t the crafts person sign it?”

“Because they didn’t like it.”

“Maybe they did not think it was important.”

“Maybe they didn’t know how to write.”

There is the date, around 1860. And a place, the south. Put these two facts together and we can make a very sure guess that this object witnessed slavery. At this time it was illegal for any person who was enslaved to know how to read or write because white slave owners were concerned it would empower captives to break free (which, even though a barbaric reason to oppress, was true for Frederick Douglass). However, some people who were enslaved, such as Dave the Potter, did know how to read and his story is told here too because this larger pot in the case is his, his name etched in the clay. Dave the Potter lived in Edgefield Co., South Carolina, the same place where these face jugs originated.

Though the importation of people was outlawed throughout the States in 1808 (the slave trade continued well into the nineteenth century until slavery was finally abolished with the end of the Civil War in 1865). Exchanges continued and the last known illegal ship to smuggle captives for enslavement was the Wanderer. Traveling from West Africa, the ship landed on Jekyll Island, Georgia in 1858. Rumors abounded on the east coast that the former luxury yacht had been altered to secretly carry kidnapped Africans and high rewards were promised for information. Still, the vessel made landfall and then sold the over 400 captives on board, the oldest 38 the youngest born en route over the Atlantic Ocean.

Once the Wanderer arrived on Georgia's coast the ship sailed up the Savannah River to plantations on the coast and inland including Edgefield, South Carolina. Situated on the fault line, these businesses had a natural supply of clay making the area, even today, well known for its ceramic production and artists. And then, most of these artists were enslaved.

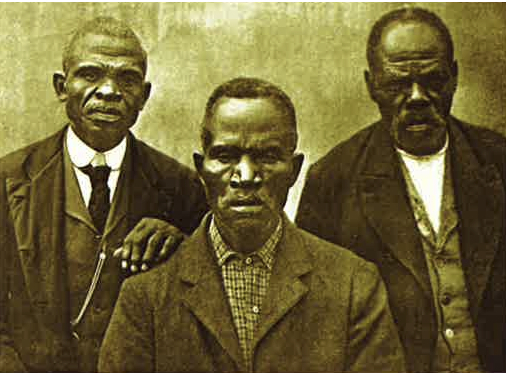

Three of these artists, captured as teenagers, were known in Africa as Cilucangy, Pucka Geata, and Tahro (pictured from left to right). Depicted in this photograph taken fifty years after their arrival, at least outwardly, as assimilated to Western culture. Their new names Ward Lee, Tucker Henderson, and Romeo. Tahro (Romeo) worked in the ceramic factory in Edgefield, it was when he joined the workforce that face jugs began to appear. Therefore, it is theorized that he is responsible for either bringing or continuing this West African ceramic tradition to North America. Although without a maker's mark, this cannot be confirmed.

However, let’s not get so enveloped in an artist's biography that the art object itself is lost, no matter how intriguing or tragic. We have strayed from the focus. So, with information compiled, let’s look again at the object.

We have observed, developed understanding through context as we dwell on it’s place in history, now we will delve deeper into its meaning - what did the artist wish to express? To do so, let's look again to the objects.

Unidentified maker from Edgefield District, South Carolina, Face jug, ca. 1860

“How do you think this object functioned?”

Like their makers, uses for these vessels are unknown.

“It was used for a ritual, or maybe has special power.”

“Was it a portrait of someone they knew?”

“I think it was used for storage, to hold something small.”

“Maybe it was just a joke, like a caricature of a person.”

The professor offers an opinion, “These people were enslaved, they were taken far from their homes and forced to live very hard lives away from their families. These jugs are expressions of their anger and pain.”

There are many theories based on what these gruesome expressions mean, and all of these answers have merit.

Many white potters use similar containers to hold liquids unfit for children. Scholars believe these specific vessels were not meant to startle the young but evil spirits, a talisman for protection. Kaolin, a white clay familiar to West Africans for its use as a sacred material, is found naturally in the South Eastern US. It is used here to decorate the eyes and teeth suggesting the spiritual qualities and ritualistic use of these objects.

The plantation owner in Edgefield noticed his workers created upsetting faces out of clay in their free time from excess clay, made small enough to fit into tight spaces available in the packed kiln. Perhaps these were a way for artists who were enslaved to get out frustrations, making ugly jugs that resembled their masters, a pastime their owners passed off as whimsical.

The expressions we study here must not be ignored - raised, tense brow, bulging eyes, flared nostrils and clenched teeth - the embodiment of such strong emotions could confirm yet another theory. Perhaps they marked graves. With little means to provide headstones for loved ones laid to rest, those greiveing while enlaved fashioned markers from wood or found materials given by their owners. And more recently, shards of face jugs have been found in surrounding burial grounds.

Our interpretation of a work of art would not be complete without contributing our own experiences. Just as a work of art's presence affects us, our experiences affect the interpretation we make of the object. We do not, and should not, leave our ‘lived lives’ at the museum threshold. After all, art is the truest expression of human feelings. How can it function without us contributing ours?

Do these face jugs convey to the viewer the harmful substance they could hold? Or are they the physical manifestation of grief? If not an expression of sadness of a loved one, perhaps loss of home or loss of identity? Or could it express the strain and horror of captivity? Exhaustion?

Once the research is done, conjecture put to the side, we have only our insight within the presence of this significant object to aid our understanding. How does this object affect you, what is your interpretation?

Todd, Leonard (2008). 'Carolina Clay: The life and legend of the slave potter Dave' (pp. 143-4). New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

Wells, Tom H. (2009). 'The Slave Ship Wanderer.' Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Photographs courtesy of the Georgia Museum of Art.